At nine o’clock in the morning of Sunday 13 April 1919, a peaceful crowd of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims gathered since midnight in the grassy area of just over two hectares, a sort of large square, the Jallianwala Bagh, in Amritsar, city of Punjab, north-western region of India, to celebrate the Baisakhi, the traditional Sikh spring festival. The tension has been growing in India, after the application of the Rowlatt Act: serious episodes of violence against people and things have occurred in many areas of India, and in particular also in Punjab.

Soldiers open fire on the crowd

Colonel Reginald Dyer, a British officer with the experience of the Great War behind him, learned from his intelligence service that at that time at 16:30 a meeting would have been held to protest the repressive measures in place, and had it banned.

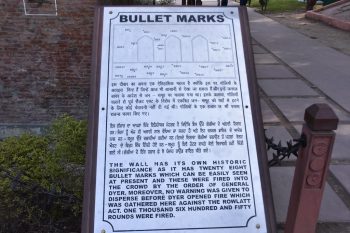

About an hour after the time scheduled for the meeting, the English colonel arrives with a contingent of troops composed of the second company of the 9th Gurkha Rifles, the 54th Sikh and the 59th Sind Rifles, fifty of which are armed with a .303 Lee-Enfiled rifle with revolving-sliding shutter; they are also accompanied by two armored cars with machine guns in the turret, which however cannot enter the square as it is surrounded by buildings three or four stories high, with only a few accesses, equipped with gates, some of which are permanently closed.

Dyler acts without no hesitation. He will then explain that his purpose “was not to disperse the meeting, but to punish the Indians for their disobedience”. In fact, Dyer orders the fire to be opened by directing the shooting at the points where the crowd is most concentrated: his soldiers shoot for about ten minutes without interruption, pulling over 1,650 rounds, until they have almost completely exhausted their ammunition.

Toll of a massacre

The crowd, variously estimated at between six thousand and twenty thousand people, despite not having committed any violence, has no chance: the official death toll from the massacre speaks of 337 victims, including 41 boys and even a six-week-old baby. A subsequent Indian Congress inquiry will bring the budget to over 1000 victims. Immediately after the event, the governor of Punjab, Michael O’Dwyer, proclaims martial law, while in India the event raises an indignation that will leave a trace indelible in the history of the country. The great Indian intellectual Rabindranath Tagore, after receiving the news of the massacre on 22 May, publicly renounced the title of knight received by the English, writing to the British viceroy: “I wish to be free from any particular distinction, alongside those of my compatriots who, for their so-called insignificance, they are exposed to suffering inadmissible degradation for any human being “.

Shortly before his death (1941), in a decisive period of the Second World War, Tagore would have said, in response to a question from an English MEP: “The English exploit the starving Indian people. While England is thinking of getting supplies of food to the British Isles by all means, the Indians are not given even a handful of rice. If the English are opposed by the Indian population, this does not depend on the fact that it is the enemy of foreigners, but on the fact that the English have abused the trust of India, sacrificing the welfare of millions of Indians to fill the pockets of some capitalists. England should at least have the decency to remain silent and not to blame the anti-British movement on the Indian people.”

The consequences of Amritsar

The Amritsar massacre would have paved the way for India’s long struggle for independence, in which, alongside to Gandhi‘s noble address towards non-cooperation and non-violence, much more bloody methods of struggle would have been present and active: on 13 March 1940, in fact, at Caxton Hall in London, an Indian independence activist from Sunam, Udham Singh, who had been an eyewitness to the massacre, shot Michael O’Dwyer, the aforementioned governor of Punjab, who publicly endorsed Colonel Dyer’s conduct.

Sentenced to death, then hanged in July 1941, Singh he declared to the court:

“I did this because I felt hatred against him. He deserved it. He was the main responsible. He wanted to bend the spirit of my people, and I bent him. For over twenty-one years I have been trying to get revenge. I’m glad I got it. I don’t fear death. I’m dying for my country. I saw my people starving under English rule. I protested against it, it was my duty to do so. What greater honor could have been reserved for me to die for my country?”