Talks between the US government envoy, Zalmay Khalilzad, and representatives of the Taliban guerrillas are underway in Qatar: the latest press reports speak of a possible agreement, which would provide for the withdrawal of US troops from the country in exchange for the ceasefire and the disengagement of the increasingly undefined al Qaeda from Afghanistan.

Meanwhile, the Taliban’s bloody attacks against the Afghan government continue, which today control at least half of the country, awaiting the umpteenth elections scheduled for September, which only serve to make the Western-backed government appear democratic.

The Great Game

Beyond the diplomatic skirmishes and media claims, the gigantic war operation that the US and its allies, including NATO, have set up in Afghanistan since December 2001 is about to end with a significant defeat of the Westerners, not dissimilar to what happened to the United States in the 1970s in Vietnam.

It may also be useful in this case to go back a century, given that in August 1919 the so-called third war between Afghanistan and Great Britain ended in Rawalpindi, with the homonymous agreement.

The context is that of the so-called Great Game, which the British and Russian empires developed in Central Asia during the nineteenth century: the British to consolidate their control of the Indian subcontinent, the Russians to reach the so-called “warm seas”.

It was the British who scored the greatest successes in this diplomatic, espionage and economic conflict: firstly with the Treaty of Gandamak (1879), with which they assumed control of Afghanistan’s foreign policy, then with the imposition of the so-called Durand Line (1893), a boundary traced on the basis of pure strategic-military criteria, without any consideration of the historical and ethnic conditions actually existing on the ground.

Finally, in 1907, the Anglo-Russian agreement determined the division of Central Asia into the respective zones of influence of the two empires, creating a balance in which Afghanistan, although included in the area of British influence, actually assumed the condition of “buffer state” between British India and the Central Asian area of influence of the tsarist empire.

The effects of the Great War

Just as in the case of India, even in Afghanistan it was thought that the Great World War should lead to changes, all the more in the light of the statements of principle proclaimed by the Entente powers.

On 28 February 1919, following the killing of the emir Habibullah, his son Hamanullah Khan ascended to the Afghan throne, particularly influenced by his father-in-law Mahmud Tarzi (1865-1933), a secular, nationalist and modernist politician, writer, journalist, belonging to the Pashtun aristocracy of Kandahar, leader of the Afghan Youth movement, who was clearly inspired by the Young Turks, promoters of the reforming and modernizing movement in the Ottoman Empire: Tarzi was appointed foreign minister by the new sovereign.

It was the massacre of Amritsar in India, of which we have already spoken, to arouse the indignation of the new Afghan emir, who did not hesitate to invoke the holy war against the English, addressing the tribal leaders, two days after the massacre, with the words : “Take up arms, the time has come!”

Also decisive in this attitude of the young Emir was the resentment for the lack of recognition of the English with respect to the neutrality strictly observed by the Afghans during the conflict, in exchange for which at least the end of British interference in the country’s foreign policy was expected: the viceroy of India, Lord Chelmsford, had instead refused to renegotiate the Anglo-Afghan agreements, as was expected to happen when a new emir was installed.

No doubt he also played the role that the collapse of the Tsarist empire was setting in motion all of Central Asia, in which the civil conflict in Russia between “reds” and “whites” was accompanied by the autonomist thrusts of Islamic Turkic countries.

Third Anglo-Afghan War and Rawalpindi Treaty

The war, which broke out in early May 1919, saw the ready use by the British of all the new war resources whose use had been well tested on the European battlefields: about thirty aircraft, some tanks, and substantial forces of heavy artillery was used massively against the Afghans, to the point that, according to the sources of the time, a ton of explosives would have been poured on Jalalabad in a single day.

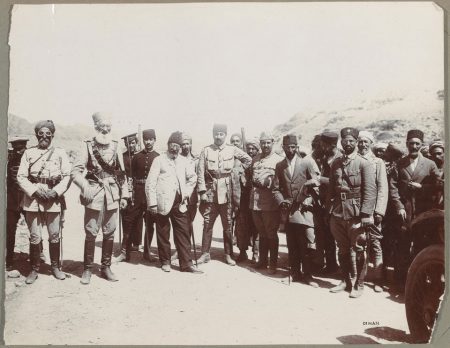

Despite the resistance offered by the Afghans, and the many problems that the British had also among the troops of their own local contingents, on 2 June the supreme Afghan commander, Nadir Khan, was forced to ask for a ceasefire and the opening of negotiations .

The result of the negotiations, formalized in the Treaty of Rawalpindi, signed on August 8th 1919, did not present at first sight particular novelties: the five very short articles of the text had as a central theme the re-establishment of good relations with British, which would have been re-examined after six months, as well as slight penalties for the Afghan government for its reckless initiative (the Afghans could no longer import weapons as in the past, the arrears of subsidies that the English paid to the deceased emir were confiscated …).

Afghan independence and English diplomacy

The real novelty was however represented by a letter that the British representative A. H. Grant was pleased to send at the request of the Afghan Foreign Minister, and which deserves to be reported here in full:

”You asked me for some further assurance that the Peace Treaty which the British Government now offer, contains nothing that interfered with the complete liberty of Afghanistan in internal or external matters.

My friend, if you will read the Treaty carefully you will see that there is no such interference with the liberty of Afghanistan. You have told me that the

Afghan Government are unwilling to renew the arrangement whereby the late Amir agreed to follow unreservedly the advice of the British Government in regard to his external relations. I have not, therefore, pressed this matter : and no mention of it is made in the Treaty. Therefore, the said Treaty and this letter

leave Afghanistan officially free and independent in its internal and external affairs.

Moreover, this war has cancelled all previous Treaties.”

In this way, albeit with all the ambiguity that British skilled diplomacy is traditionally capable of, Afghanistan formally acquired its independence from the British Empire.

Independent Afghanistan and Italy

How limited it was, however, was soon seen. The dream of Afghan independence was immediately crowned with the realization of the commercial and diplomatic agreements that the Afghan government established in 1921 with Italy, first among all the Western Powers.

But this full recognition of the independence of the Central Asian country by the Italians nevertheless aroused the ire of Lord Curzon, British Foreign Minister, who did not hesitate to observe that the Italian démarche, which followed the collaboration between Italians and Turkish Kemalists, denoted an attitude of Italian foreign policy hostile to the English Empire.

A clear sign, as the American diplomats observed in those circumstances, that the British, despite the historic agreement in Rawalpindi, still considered Afghanistan part of their “sphere of influence”.