It was clear from the start that the peace of Versailles was not destined to bring peace to Europe. The most obvious, but little known, case was the conflict that broke out between Romania and Hungary at the end of July 1919. Interesting conflict, as revealing of how the winners of the Great War, especially France, conceived the peace just reached.

Bolshevism in Hungary

One of the effects of the dissolution of the Hapsburg Empire in Central Europe was the birth of the republic in Hungary, with the so-called Cristantemi Revolution of October 30, 1918, which brought to power a pro-Western Social Democratic government, which however was not recognized by the Allies.

He played the French desire, also accepted by the British, to favor the Czechs and Romanians at the expense of the Magyars, with the aim of establishing an area of French influence in defense of the Central European German area, on the one hand, and on the other , to create an anti-communist sanitary cordon that from reborn Poland encircled Soviet Russia to the west: the latter reason that the Allies had already intervened, with over 150 thousand men, variously displaced, in support of the “white Russians” in struggle against the Red Army of Trotzsky since the summer of 1918.

The crisis plummeted in Hungary when the allied plenipotentiary in Hungary, Lieutenant Colonel Ferdinand Vyx, presented a note of the Entente to the Hungarian government with which he was told to withdraw from the previously agreed borders with the armistice signed in Belgrade, in order to yield further territories to neighboring countries, such as Slovakia to the Czechs and Transylvania to Romanians.

The so-called Vyx Note caused the fall of the pro-Western government of Mihály Károlyi and the rise of a pro-Bolshevik orientation government, chaired by Sándor Garbai: on March 21, 1919 the so-called Council Republic was born, the first example of a Soviet country outside of Russia, in which, although with the role of Minister of Foreign Affairs, the most charismatic politician was the communist Bela Kun, determined to establish the dictatorship of the proletariat on a Leninist model, with the consequent collectivization of agricultural properties, banks and industries.

The red danger

As early as March 24, 1919, the French began, together with the one already in place against Bolshevik Russia, military planning to counter the new Hungarian regime: it was thought to advance over Budapest by three infantry divisions and one cavalry division provided by Serbia, of four Romanian divisions and of two divisions and a French cavalry brigade currently headquartered in Szeged, in Hungary itself, where, among other things, a Hungarian counter-revolutionary government was installed.

This plan encountered several difficulties: first of all the Serbs were very lukewarm at the idea of embarking on a military campaign against Hungary; secondly, a much more serious reason, the French troops, particularly the fleet sailors at anchor in Odessa, began to show signs of fraternization with the Bolsheviks who were supposed to fight 1.

The French hastily withdrew their naval units from Ukraine, while a convoy of 100,000 allied soldiers, destined to support the anti-communist white armies, was directed to Romania, to whose army the task of guarding the border on the Dnjepr against the Army was already due. Red, along with the usual French.

In this way, it was Romania that appeared to be the best candidate to defeat the Hungarian government, given that the Romanian claims against Hungary were considered all in all a fair compensation for the very high price paid by this country for having sided against the Empires Central during the Great War: after all, a secret treaty signed by the Entente with the Romanians in Bucharest in 1916 ensured Romania vast territorial acquisitions, most of them at the expense of Hungary.

The Romanian-Hungarian conflict

Allied planning was then focused on the use of Romanian forces against the Hungarian communist regime, in order to overthrow it; but, in the same days, the allied representative in Hungary, the South African prime minister Jan Smuts, started a negotiation with the government of the Republic of Councils – with all the evidence for the sole purpose of gaining time to organize its overthrow.

The Romanian troops meanwhile advanced to the line indicated by the Nota Vyx, but on April 26 they informed the Allies in Paris that they wanted to cross it until they reached the Tisza river, which they did immediately and successfully. The situation, however, was complicated on the one hand by the intervention of the Russian Bolsheviks on the Dnjepr, which required the movement of Romanian troops on that front; furthermore, the Hungarians took advantage of Russian support to engage in a conflict against the Czechs with good results in an attempt to recover Slovakia.

This Hungarian move allowed the Western Allies to present an ultimatum to Bela Kun on 8 June 1919, urging them to suspend military operations against the Czechs and to withdraw from the occupied territories. The Hungarians, unexpectedly, accepted the request of the Allies, signing the armistice with the Czechs on June 23rd.

The Romanians, whom the Allies had requested to withdraw within the borders defined by the Bucharest agreements, refused instead to do so until the Hungarians had demobilized: on their side they had French support, so on 11 July the Council allied to Paris he ordered Marshal Ferdinand Foch to prepare a coordinated attack against Hungary, using perhaps Romanian, Serbian and French.

The Hungarians, despite their numerically inferior forces (just over 50 thousand men), took the initiative first, attacking on July 20: but, after some initial successes, they suffered a counterattack on July 24 with which the Romanians, strong of nearly 100 thousand men, within a few days, they were able to cross the river Tisza, opening the way to Budapest, which was occupied on 4 August 1919.

Fall of Bela Kun and “white terror”

On 1 August the so-called Hungarian Council Government resigned and on 2 August Bela Kun fled to Austria and from there to the Soviet Union.

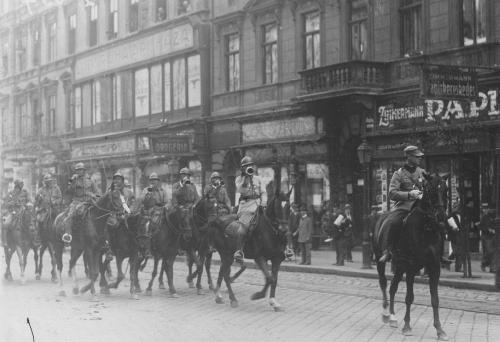

With the Romanian troops, also the counter-revolutionary troops of the Szeged government entered Budapest, commanded by the Hungarian Miklós Horthy de Nagybány, who had proved himself, even against the Italians, as the last commander of the Austro-Hungarian fleet . Thus began the so-called “white terror”, a fierce anti-communist and anti-Semitic repression, with which it was intended to respond to the “red terror” previously established by the Republic of Councils: even if Horthy’s role in the action of the anticommunist paramilitaries is still the subject of discussion, the repression lasted for almost two years.

The Romanian occupation, however, lasted until the early months of 1920 but was particularly burdensome as Hungary had to cede its entire war industry to Romania, half of its rolling stock (800 locomotives and 19,000 wagons), thirty percent of the livestock and agricultural equipment, 35 thousand cereal and forage wagons.

This clash between the states of the Balkan and Central European countries, as can be seen, outlined some aspects that would have characterized the entire dramatic first post-war period: the Fourteen Points, thrown on Europe as instrumentum regni, were overwhelmed on one side by the exasperated territorial ambitions of the ethnic-political mosaic born of the disintegration of the Central Empires and of Russia; on the other, they were also overwhelmed by the affirmation of anti-Bolshevism in defense of the model of a Western democracy not easily applicable in Central-Eastern European areas.

This unprecedented mixture fueled the birth in continental Europe of a direct opposition between nationalist and communist mass movements, which would have conditioned the whole post-war history. In Italy, for example, precisely the Allied intervention in Hungary provoked street protests, in particular on the part of the Socialists, in a climate already made inflamed by the “strikes against the high prices” exploded between June and July, and by the nationalist thrusts that manifested with violence in the Fiumans Vespers.

The policy of Versailles therefore spread seeds of violence between states and within European states, whose effects would soon be manifested.

- G. Colonna, Ucraina tra Russia e Occidente, Edilibri, Milan, 2014, p. 14.↩