Until a few years ago, those wishing to understand something of the tragedy of the people and of 20th century German culture could find a good guide in the autobiographical novel by Ernst von Salomon, A German destiny, in which one could follow this tragic journey from a point of mainly political view.

In recent years, perhaps as early as just five years, contemporary Germany seems to have noticed an even more tragic aspect of its history – moving from a political view to an art one: the emblematic case is that of Emil Nolde (1867-1956), whose in these weeks the first exhibition that seems to be publicly aware of this German drama is dedicated to Berlin.

Nolde and Nazism

For those not familiar, Emil Nolde is undoubtedly one of the most important painters of contemporary Germany, who in his long life had the luck (… luck?) of crossing the whole terrible first half of the German 20th century, with all its contradictions: it was a protagonist of expressionism, but it entered into a serious collision with the German expressionists; fervent nationalist and anti-Semitic, enthusiastic adherent to the NSDAP, but soon put on the index by some high exponents of the regime, including Hitler himself, as we know an artist also in his youth; after the end of the war, he is considered, until nowadays, an eminent persecuted by the Nazis. It seems impossible, yet Nolde has lived all this.

The exhibition at the splendid Hambuger Banhof in Berlin really does reflect why, alongside the (beautiful) works of Nolde, documentation is presented in a simple but effective way on this rugged, never politically correct path of the great artist.

In addition to his undoubted artistic value, we highlight the talent with which, partly himself, but certainly much more the many authoritative critics who courted him, made of a fervent nationalist, anti-Semitic and supporter of National-Socialism, the symbol of the persecuted artist from totalitarianism: to the point that one of his paintings stands out in an official photo behind Angela Merkel and Barak Obama at a meeting in the Chancellery of the democratic Federal Republic of Germany, a few years ago (have they taken it off today? We don’t know …) .

If we talked in purely political terms, there would be very little new: we Italians have long been aware of how much of our people has quietly changed jacket from the most fascist access to the most rabid anti-fascism. Even in the field of culture, the examples of waste.

But in Nolde’s German destiny, in our opinion, there is something far more important to grasp than this human tendency to adapt to atmospheres or political conveniences: this is why we hope that the undoubtedly courageous and honest Berlin show can ignite if not a debate at least a reflection finally unprejudiced not only on German history but on the relationship between art and politics.

Classicists and Volkisch

We begin to understand that the adhesions to the totalitarian phenomena of the last century cannot be judged with today’s assurance, because they had deep roots in a spiritual, rich and contradictory climate, in which powerful ideal forces were condensed and schematized in forms, those policies precisely, that they could not support all the novelty, strength and multiformity.

From this point of view, the Nolde story is interesting, because it turns out that even National Socialism was not as monolithic as we are used to judging it, especially when it faced the ideal production par excellence, the artistic one.

Nolde in fact found supporters and opponents among several of the most important exponents of the NSDAP: it would therefore be to understand for what reasons a Goebbels sympathized for Nolde and a Rosenberg not, for example. Some valuable scholars believe that Nolde was close to the positions of the so-called volkisch nationalism, which, after having fueled the left-wing National Socialism, was marginalized starting from the violent purge of the SA on the Night of the Long Knives in June 1934: something that could explain just the progressive marginalization of the artist after 1934.

It is also clear that Nolde saw in National-Socialism what evidently saw us also in people much simpler and less highly inspired than he: the affirmation of Germanism, an irrationalist vitalist romanticist, with respect to the refined culture of French decadence; the cult of the roots of a mystical and ascetic Middle Ages, taken up with the Protestant fury of a Martin Luther; roots that were also referable to the concrete forms of Germanity, those of Tacitian Germany 1 and of the magical and elementary nature of the Nordic landscapes.

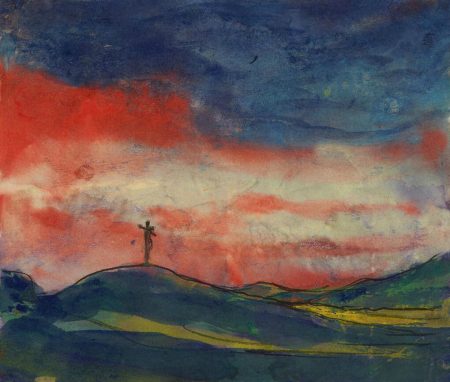

All this in Nolde is clearly legible in his paintings, particularly in the vibrant landscapes of essential colors and chromatic contrasts; and it is sufficient to explain, albeit obviously not to justify, its radical anti-Semitism, dictated by the fear of a foreign cultural and economic dominance, also in the artistic field, to its Germanism.

The freedom of the artist and politics

The German tragedy is very clear, therefore, in Nolde. He started from an eminently spiritual impulse, when he wrote:

«Images are spiritual creatures. The spirit of the painter lives in them. The best ones are the most demanding». 2

He spoke very clearly in his autobiography about, for example, his paintings on Pentecost, those that less liked the Nazi neoclassical setting like Hitler himself:

«Again I returned to the mystical depth of the divine human existence. The Pentecost painting was sketched. Five of the fishing apostles were represented in ecstatically and supersensibly receiving the Holy Spirit.» 3

The crude simplicity of forms, which appeared “degenerate” to his censors, corresponded in him to the powerful genuineness of the souls of the Apostles, completely free from the refined intellectualism of the Greek-Roman elites; and for him this was also the spirit of Altdeutsch, the ancient Germanic culture, not corrupted by decadent occidentalism, with a strong connotation of a free and entirely interior religious experience.

«I followed an irresistible desire to represent a profound spirituality (religion and intimacy) without however any will or knowledge or rational explanation. (…) Following these sensations, I painted my sacred paintings. But beyond the contrast between light and dark and between cold and warm colors and together with the representation of spiritual and religious figures, I was led to make a difficult and intimate reflection on religion, a true and desperate spiritual meditation that would have could take me to total madness. (…) If I had strictly adhered to the Bible in a literal sense and to the rigidity of dogmas, I am sure that I would not have been able to paint these images (…) which I conceived so intensely. I was obliged to be free from an artistic point of view: not having God in front of me as an upright Assyrian legislator, but God in me, ardent and sacred as the love of Christ. With [these] paintings [religious] my transition took place from the external beauty perceived according to the rules of optics to the inner values that are the fruit of feeling.» 4

We can say that here the symptomatic manifestation of the conflict between art and politics is manifested: the drama of all those artists who wanted, by sense of belonging to their time and their people, to become engagé (or “organic” as Gramsci said) – but that in reality they could not find in the Schmittian “forms of the political” any actual location for their free inner impulses.

The drama of Nolde is therefore the drama of all those who, with a sense of a civil duty, sought in politics a completion to their spiritual artistic vocation, and who instead found themselves rejected by the rigidity of ideologies, or conditioned by the need to to adapt to the nature of the “politician”, in a word nailed to the unanimous logic of power.

The censures by totalitarians, but not only …

However, we must add that it is too easy to make this incompatibility between artistic and political a phenomenon only typical of totalitarianism – a point that we hope will not escape at least from the most discerning visitors to the beautiful Berlin exhibition. The issue affects all modern societies, in which art and politics should remain mutually independent, if we really want to talk about freedom.

In the ancient world, from before the times of Alexander the Great, when as many as 39 statues could be commissioned to a Lysippus to commemorate the fallen in the victory of the Granico, it was in a logical way that art was an expression of power – when everything was integrated into a unitary spiritual vision.

From then until the present day, every political or religious story that has had the habit of legitimizing itself culturally has always sought the artist from whom to be celebrated.

But, in more recent times, in which the role of the artist has become increasingly individualized, to the point of enclosing an intimate dimension, it is understandable that the celebratory space of politics has been left to the “militant” artists or simple opportunists. The famous perte d’aureole that Baudelaire wrote about, so to speak.

Today’s politicians, having exhausted the great mass movements, prefer to offer themselves to the public with the cultural stature of a joke or a post on social media.

It can be understood that, as a consequence, at least since the 1970s, any artist has felt the need and almost the duty to feel outside the box or even against the systems, to demonstrate that he is exercising his freedom. That they succeeded, of course, is another matter. The fact is that nowadays the situation of artists, although not rosy, is therefore very clear: art can exist only if it is independent of politics.

Those who think they can continue doing politics with art should realize that, since the parties themselves have renounced an ideological identity, artists today are finally free to live in their own purely ideal dimension, without having to align themselves with any party, especially as these today determine their own uncertain identity only through references to GDP growth or spread swings.

There is however, as always with full freedom, an element that could originate, and perhaps already originate, dramas of a new kind: while Nolde could still find ideal references that made him feel part of a whole, for today’s artists, these references have probably disappeared – hence the question of how the artist can be placed in the human consortium to avoid becoming, with all its splendid interior freedom, a foreign body to the society in which he lives …

Meanwhile, we limit ourselves to wishing however that, rediscovering the Nazi past of Emil Nolde, it is not decided to put it to the blacklist of political uncorrectness, just as the neoclassical Nazism made with him when he was suddenly discovered as a “degenerate” artist.

- A Most dangerous Book is the title of the beautiful study by Christopher B. Krebs on the bibliographical history of the Tacitian work, published by W.W. Norton and Compton, New York-London, 2011.↩

- E. Nolde, Mein Leben, 1934.↩

- E. Nolde, Jahre der Kaempfe, Berlin, 1934, pp. 105.↩

- E. Nolde, Mein Leben, Cologne, edited by Manfred Reuther, DuMont, 2013, p. 194-195.↩